At long last, the General Accounting Office (GAO) has been asked to investigate the revolving door personnel changes that occur under every administration between top-level people working on Wall Street who enter the very federal agencies that provide oversight for their former firms.

At long last, the General Accounting Office (GAO) has been asked to investigate the revolving door personnel changes that occur under every administration between top-level people working on Wall Street who enter the very federal agencies that provide oversight for their former firms.

This revolving-door scenario is common at all the major federal agencies that have regulatory oversight over major Wall Street firms and institutions. These regulators include the Federal Reserve, Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) and other lesser-known agencies that regulate insurance.

Matching the former Wall Street affiliation of top regulators who formerly worked on Wall Street would be a great parlor game were it not for the blatant conflicts-of-interest these former financial industry employees routinely show.

Nor is the practice of “regulatory capture” unique to the financial services industry.

In a March 4, 2016 Wall Street Journal story, the head of the GAO said:

“We currently do have some ongoing work looking at the concept known as regulatory capture. We’re in initial stages of outlining that engagement,” Lawrance Evans, director of the GAO’s financial markets and community investment division, said in an interview.

“The agency will conduct ‘an assessment across all financial regulators, and the Federal Reserve will be one institution,’” he said.”

While this GAO investigation is unique, the idea of having trusted ex-employees move into government positions to drive business and affect regulations is not new. Former President Dwight Eisenhower recognized the practice in 1961 when he first used the term “military industrial complex” to describe how his former Army officers were entering the growing military supply business and then using all of their former Pentagon contacts to get exceptional information about the very competitive bidding process.

The stakes are just as high in the competitive financial services industry as more arcane rules and regulation can mean huge changes in established proprietary trading, cash required for trading, additional disclosures, exempting some financial instruments from oversight and keeping better trading records. Making changes to any one of these areas represents billions in potential profits or changes to established lucrative markets.

Minimizing Risk Through Patronage

If there is anything Wall Street hates above all else it is regulatory uncertainty. Markets ebb and flow, but it is much easier to control the human-driven regulatory process by getting former employees places into high positions at key regulators. That, combined with incessant lobbying, can drive the direction of where financial institutions want the regulatory landscape to look like.

So it is no wonder that this 2012 list of 50 former employees from Goldman Sachs alone working in the Obama and Bush White House administrations is startling. Of course, the biggest names on

the list are Hank Paulson, former Goldman Sachs CEO and architect of the 2007 TARP bank bailouts and Tim Geithner, former Secretary of the Treasury, former President of the New York Federal Reserve and a former managing director of Goldman Sachs. But others on this list have held positons at every major agency and advisory body that covers Wall Street.

One reason why there are so many Goldman Sachs employees who chose public service is not because of their altruism and desire to do the public good, it is because of money. In a little-known piece of lobbying clout, lobbyists got Congress to work out a very favorable tax deal for Goldman Sachs employees who work for the government. In exchange for the government service, Goldman executives that had options got a better tax deal than if they did not enter government service.

But it is not only Goldman Sachs. Citi, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley also reward executives who enter government service. In this 2015 New Republic story, the payouts in bonuses and special incentives paid by these major firms to their executives are designed to deliver pro-industry decisions.

Is the System Rigged?

While most astute political and financial industry observers know the system is riddled with the revolving door bureaucrats, the New Republic article states that the system is near seamless between regulators, industry officials and even politicians:

“[The practice of regulatory capture] fuels the revolving door between banks and the government,” said Michael Smallberg, an investigator for the Project On Government Oversight (POGO), whose 2013 report detailed these types of compensation agreements.”

Nor is this just limited to those who worked on Wall Street. Eric Holder, the former U.S. Attorney General (2009 to 2015), took a leave from his corporate law firm, to serve in the White House and then returned to his old corner office that was reserved for him when he left the White House. Holder never missed a paycheck and he will collect at least two hefty pensions.

Holder moved back to his former law firm, Covington & Burling, a corporate law firm known for serving Wall Street clients, where he worked from 2001 to 2009, immediately before he became

U.S. Attorney General. The law firm was so confident that he was returning that it kept his corner office vacant for his inevitable return. In the process, Holder most likely took a pay cut for the $2 million he was probably making at his law firm (my estimate) to the $200,000 salary he received from taxpayers.

Then there is Gary Gensler who served in the Obama Administration as Commissioner of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. He is a former Goldman Sachs Partner and Co-head of Finance and has the distinction of working to push through the Commodities Futures Modernization Act of 2000 (passed in the Clinton Administration) that famously deregulated the area of over-the-counter derivatives, including credit default swaps, that were widely cited as being a major cause of the financial crisis of 2008 and the subsequent 2008–2012 global recession.

Go Go GAO

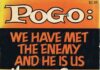

So as the GAO launches a long-overdue investigation of regulatory capture, it is one more example that the tide of public opinion is shifting ever so slightly. Obama missed a great opportunity when he failed to pursue those executives that certainly caused the 2008 recession that still lingers today. It is a stain on Obama’s record and it has hurt Democrats in the 2016 presidential campaign.

But those interested in Wall Street reform should not get too excited. The GAO, whenever the report is completed, will shed more light on the cozy relationships between regulators and the corporations they are supposed to supervise. It may quantify the costs of flawed regulation or better yet, find the tit-for-tat and quid pro quo that underlies this whole system. Maybe the report will shed more light on Bernie Sanders’ description of Wall Street’s business model being based on fraud.

But this is an entrenched system where billions are at stake. The system will be hard to dismantle. Even pundits who follow presidential candidate Hillary Clinton, who made noise on the campaign trail about the criminal behavior of Wall Street executives, said that a favorite for the top spot of U.S. Treasury Secretary would be Larry Fink, the CEO of BlackRock, the world’s largest investment manager. Of course, he would have no connection to Wall Street and would be above any form of regulatory capture. After all, he’s only human.