“To put it badly, there are two ways to become wealthy: to create wealth or to take it away from others. The former adds to society. The latter typically subtracts from it, for in the process of taking it away, wealth gets destroyed.”

–Joseph Stiglitz, Nobel Prize Winner in Economics, 2001Pity the middle class.

Once the esteemed goal for millions seeking financial security and hopes of greater prosperity, the middle class has come under attack from a variety of sources all intended on diminishing its collective wealth.

Attacks on the middle- and lower-class come in different forms—the elimination or reduction in earned pensions; higher costs for health care; the denial of access to free education, police and fire services; the increased privatization of previously available free or subsidized public services; and the reduction in state-funded welfare programs. All this is being done through the collective force of what economists call “rent seeking.”

At the macro-level, banking and recessions are a more ever-present and insidious means of eliminating wealth which has been painfully accumulated, over decades, by the middle- and lower classes. While these banking crises and recessions are a regular feature of capitalist systems worldwide, accurate and thoughtful discussions about these crucial capital market events are carefully avoided by financial professionals advising their most vulnerable individual clients.

This is no accident. Discussing recessions and bank failures is dangerous to wealth accumulation, market credibility, and worse, there are few risk management activities which can mitigate the steep and long-lasting financial losses.

This wealth destruction has not been ignored by the most powerful banking institutions in the world. The International Monetary Fund in a September 2008 IMF Working Paper (“Systemic Banking Crises: A New Database,” Luc Laeven and Fabian Vanencia) detailed 124 systemic banking crises from 1970 to 2007 affecting 37 nations. In addition, the authors detailed currency crises, sovereign debt crises, and combinations of the two.

In coping with these crises (and coping not managing is the appropriate word), the IMF paper notes that governments and their central banks worldwide which used policies that reallocated wealth towards banks and debtors at the expense of taxpayers, also diverted taxpayer wealth upwards towards many of the same banks which caused the financial crisis in the first place. In addition, the paper said this financial assistance included “indirect costs from misallocations of capital and distortions to incentives that may result from encouraging banks and firms to abuse government protections. Those distortions may worsen capital allocation and risk management after the resolution of the crisis.”

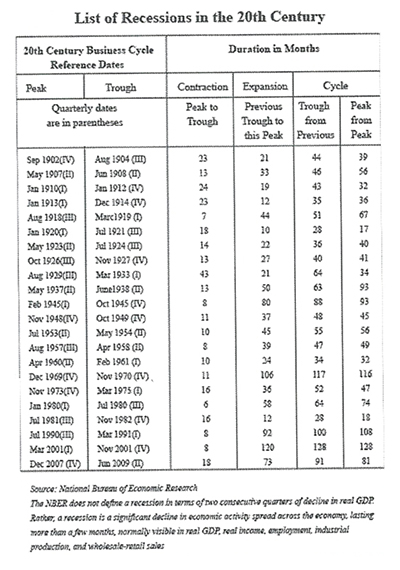

In addition to banking crises, the wealth of individual investors is destroyed by recessions, market bubbles and market crashes. As this chart shows, in the 20th Century there have been 22 recessions (from September 1902 to December 2007) with the average contraction (as measured from peak to though) of 14.6 months, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research. Economic expansions are also part of the recession cycle, but behavioral finance correctly notes that investors note their losses more than their gains.

The most recent 2008 recession affected housing more than other assets and this had an even greater deleterious effect on average Americans. The reason: housing equity is often the greatest engine of personal wealth for most Americans, greater than retirement savings accounts and pensions. When the 2008 recession destroyed housing prices, credit availability and confidence in the banking system, it destroyed trillions in housing wealth worldwide, the vast majority of it affecting individual average taxpayers.

The Reason For and the Insidious Power of Alienation

While not generally discussed, the investing public has noticed this litany of charges, investigations, indictments, wealth destruction, unbridled greed and its lack of penalty committed by the world’s largest financial institutions. The problem is that the public’s simmering wrath is unfocused. This is intentional since the media and politicians of both parties intentionally do not address the underlying causes of recessions, bubbles and criminal price rigging by the world’s largest banks. It is just part of the system.

The problem is that it cannot be discussed since the very thought of openly addressing these seemingly isolated criminal events would cause the public to lose faith in the entire financial system. This understandably occurs at the highest levels in Washington and in corporate America, but this intentional omission is also practiced daily by hundreds of thousands of financial professionals who have daily contact with individual, ill-informed investors.

The thought of telling these already gun-shy investors that wealth destruction is an inevitable part of their lifetime investing experience is a real downer, but conversely, there is no substitute for the truth.

So it is no wonder that financial professionals turn a blind eye to the inevitable recessions and more importantly, why they happen in the first place, and why Fed policy, errant banks and irresponsible regulators all work together to allow these inevitable wealth destructive activities to happen. They are needed because they are a form of wealth redistribution from the middle- and lower classes to the upper classes. This is the proverbial and ever-changing top 1%, who in the U.S. have seen income going to the top 1% doubling since 1980 from 10% to 20%, according to Oxfam. For the top 0.01% it has quadrupled to levels never seen before, Oxfam said. This is because capital dominates labor.

This has also occurred on a global level where the top 1% (60 million people) and for those in the top 0.01% (600,00 individuals) the last 30 years has been “an incredible feeding frenzy,” Oxfam said.

This gross redistribution of income has been accompanied by “the stealing back of privileges once acquired (such as pension rights, health care, free education and adequate services that underpin a satisfactory social wage) has become a blatant form of dispossession rationalized under neo-liberalism and now reinforced through a politics of austerity ministered in the name of fiscal rectitude,” according to anthropology professor David Harvey, writing in Seventeen Contradictions and the End of Capitalism.

The Failure of Financial Services Professionals

For its part, the best the financial services industry can do to address these gross economic inequalities is that over “the long-term” things will be better and investment returns will edge to their historical norms. But that is over the “long-term,” whatever that is. And that news is hardly comforting to a retiree caught in between the “long-terms.”

But people are human and their reaction to this criminal behavior and lack of social mobility is alienation. The vast majorities of investors and workers who have not seen their standards of living and wages increase since the mid-1970s are alienated and have lost their trust in the nation’s political system and financial institutions. They are isolated and estranged, but cannot often articulate it today except by latching on to misguided efforts by the Tea Party and Libertarians to push for selfish rights and more austerity, which only causes their own middle- and lower-middle-class standards of living to deteriorate even more.

In short, people are alienated because they see their upward mobility is limited, while their efforts to become freer have been sidetracked by being more dominated in our endless and insatiable consumer society. This alienation has an outlet, but it is certainly not positive. It can be negatively directed at a spouse, co-workers or internally, in the form of drug, alcohol or other forms of abuse.

It is also present in the average investor’s investment behavior. A recent survey by the Employee Benefit Research Institute’s 2014 Retirement Confidence Survey found that 34% of employees questioned did not trust the advice they received from their investment professionals, while 20% said they could not afford the advice. In both cases, alienation, lack of faith in the system and stagnant wages all worked together so that 55% of respondents could not take action on the professional advice they received, regardless of its quality.

In a consumer society, alienation works to increase consumption. The reason: when a person is alienated in their work, they are also alienated in their consumption, according to French philosopher Andre Gorz. In practice, this means people spend their hard-earned disposable income on often-unneeded consumer goods and conspicuous consumption (‘bling” in all its forms.) This is part of the confused idea of the “good life” in a capitalist society in which the “rational consumer” must buy in order to be happy.

This alienation is only aggravated by technology (in its broadest sense), which denies a person’s own sensitivities and our connection with nature. According to Gorz, “Working is not just the creation of economic wealth; it is also always a means of self-creation.”

That is the choice facing millions of Americans: Is it better to be an insatiable consumer or to seek an alternative which allows fro greater individual happiness independent of being the “rational consumer.”?