What happens when the chairman of a publicly-traded corporation is accused of insider trading?

Even worse, what happens when this top executive is the chairman of the New York Stock Exchange, the symbol of American capitalism, and the world’s best well-known stock  exchange?

exchange?

That’s the huge problem facing the NYSE now and the exchange’s response could devastate its credibility. This insider trading problem also raises serious questions related to investor confidence, corporate governance, politics, greed, regulated capitalism, and securities law, all in one place.

Even worse, it also raises problems about whether the corporate ownership of the NYSE will be less objective about self-investigation than when the NYSE was owned by its members.

Sprecher Case Raises Huge Corporate Governance Problems

This quagmire also makes it a huge corporate governance case study involving the world’s top stock exchange and the huge corporation that owns it, the publicly-traded  Intercontinental Exchange (NYSE-ICE), whose chairman and CEO, Jeff Sprecher, was named in an insider trading scheme involving his wife, Georgia Republican Senator Kelly Loeffler. The Atlanta, Georgia couple is worth an estimated $500 million to $1 billion.

Intercontinental Exchange (NYSE-ICE), whose chairman and CEO, Jeff Sprecher, was named in an insider trading scheme involving his wife, Georgia Republican Senator Kelly Loeffler. The Atlanta, Georgia couple is worth an estimated $500 million to $1 billion.

The stakes, personalities, and clash of money and political and executive power make this a great case study in how modern American corporate capitalism and self-regulation work at the highest levels.

Second, this situation raises questions about whether the US Justice Department, under Trump appointee Bill Barr, conducted a full and fair investigation.

Third, there is the issue of Sprecher’s role as NYSE chairman. The NYSE is a designated self-regulatory organization (DSRO). This means it investigates itself and does not need SEC approval to conduct investigations of its listed companies and their top officers. Self-regulation works some of the time, but it is stressed beyond its limits when the people involved are the business’ CEO and Chairman.

It’s even more complicated because Loeffler is involved in a tight Senate race in Georgia that will determine whether the Democrats get control of the US Senate at the same time the Dems have control over the US House of Representatives and the Presidency.

This means the Republicans want this issue to die, while the Democrats, especially those involved in the Georgia Senate race, want to keep this important issue alive.

Is it all about crony capitalism or, is this a legitimate trading situation that gives insight into how very wealthy people manage their money?

(To see the details about the trading involved and how the trading discrepancies, see the article here on this site.)

The Insider Trading Escape Clause

The Loeffler-Sprecher insider trading case was dismissed because the power couple was covered by an SEC Rule. It also helps that they are major Republican donors. Loeffler also is a die-hard Trump supporter who cannot admit that Biden won the election. See her deny it repeatedly in this video.

Both Sprecher and Loeffler have denied wrongdoing. The couple contends their stock sales were part of an SEC 10b5-1 plan and that they had no personal involvement in the actual individual trading decisions.

According to attorney Patrick Daugherty, senior SEC partner at the Chicago law firm of

Foley & Lardner LLP, this SEC Rule says that “if you are a corporate insider, you can enter into a plan that will allow for shares to be sold at stated intervals in dollar amounts, according to an algorithm with the trades done in a certain way. This means the corporate executive takes themselves out of making the actual timing decisions about when to buy or sell. They give control to an outside advisor or brokerage firm that is not communicating with them.

“If you do it the right way, the trades can get done even when the executive is in charge of material non-public information, so they can say the buy or sell plan was set up in advance and did not rely on any trading information that was provided by the executive,” Daugherty said.

This is not the first time Rule 10b5-1 has come under scrutiny. The outgoing SEC Chairman Jay Clayton said this rule needs to be reformed.

In a CNBC interview on Nov. 2020, outgoing SEC Chairman Jay Clayton cited the problems with the 10b5-1 trading rule because it can look too much like insider trading.

In the interview, he advocated a “cooling off period” of up to six months when company executives could sell shares using a pre-arranged, blind trading plan when he appeared before a Senate hearing. If this happened, Clayton said it would “give people greater confidence that you haven’t tried to time the market.” He called it part of “good corporate hygiene” to eliminate the appearance of impropriety, an issue that is very obvious in the Sprecher-Loeffler insider trading case.

What’s the NYSE Doing About Sprecher?

As the world’s best-recognized stock exchange and the symbol of American capitalism, the NYSE attracts the attention of many corporate governance experts. The key issue is whether the NYSE can investigate itself and its own chairman Sprecher.

The NYSE is a Self Regulatory Organization, which means it does not need SEC approval to undertake investigations of its own listed companies and its officers. Sprecher is not only the NYSE chairman, but he is also the CEO and Chairman of the ICE which owns the NYSE.

To anyone concerned about corporate ethics, conflicts-of-interest, corporate governance, appearances of impropriety, regulated capitalism, and plain-old fair play, Sprecher’s executive role in an insider trading charge alone, even when he was exonerated, is the equivalent of being sucked into quicksand or getting a lethal dose of radiation.

This is why the case has attracted the attention of Common Cause, Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics, and other elected officials.

It also is not the first time the NYSE has attracted political scrutiny and been accused of having a double standard, especially as it applied to disclosing NYSE executive compensation and other areas of transparency that applied to its member firms.

While the NYSE staff can make some claims about not wanting to conduct an investigation of Sprecher and his insider trading charges (aka job preservation), the independent directors on the NYSE’s board should take actions that protect the NYSE’s reputation for all American investors.

History shows the NYSE has made big mistakes, which is why public directors were added in the first place.

In the late-1930s, the nation was in the Great Depression and the events in Europe foreshadowed World War II, the former chairman of the NYSE, Richard Whitney (who served as NYSE president from 1930-1935), was considered one of the most arrogant foes of federal securities regulation.

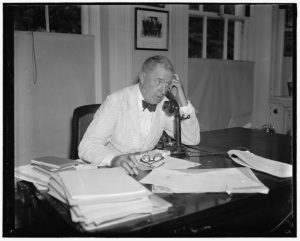

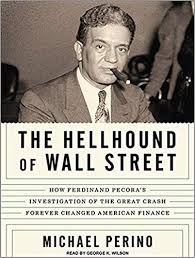

Writing in The House of Morgan, author Ron Chernow recounts how Whitney “personified the smug arrogance of the ancien regime on Wall Street. When he (Whitney) testified

about securities reform before the Senate Banking and Currency Committee in 1932, he lectured the senators on the need for a senatorial pay cut. Opposing creation of the SEC, he (Whitney) told New York Senator Ferdinand Pecora’s investigators, ‘You gentlemen are making a great mistake, The (NYSE) Exchange is a perfect institution.’”

At this time, the public had lost confidence in the banks due to mismanagement and the self-dealing of top executives. President Roosevelt urged Pecora to pressure the bankers in public hearings. Like the NYSE today, if banks were worried about the hearings destroying confidence, Roosevelt said, they “should have thought of that when they did the things that are being exposed now,” according to the Smithsonian magazine.

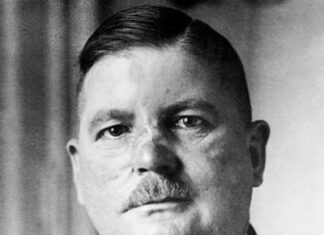

Whitney continued to oppose any reform, until eventually SEC Chairman William O. Douglas, who succeeded Joseph P. Kennedy as the first SEC chairman, reached his breaking point. In the fall of 1937, Douglas told NYSE leaders: “The job of the regulation’s got to be done. It isn’t being done now, and, damn it, you’re going to do it or we are.”

With the New Deal steamroller bearing down, NYSE Chairman Charles R. Gay became  convinced that this SEC chairman was serious. Gay did what any exchange executive did: He appointed a committee to study reform. In January 1938, the committee recommended: “a complete revamping” of the NYSE, including having a full-time paid president, professional staff, and non-member governors.

convinced that this SEC chairman was serious. Gay did what any exchange executive did: He appointed a committee to study reform. In January 1938, the committee recommended: “a complete revamping” of the NYSE, including having a full-time paid president, professional staff, and non-member governors.

It was in that atmosphere that public governors were installed at the NYSE. The role of public governors was reinforced in 1975 when regulators again mandated a public orientation towards protecting the investing community.

Sprecher’s Insider Trading Charge Requires An Outside Investigator

Securities law is arcane for a few reasons: it creates exclusivity, even among top lawyers; it often protects capital and the wealthy; it provides huge opportunities for legal maneuvering.

All this makes self-regulation suspect. The responsibility for monitoring the activities of the nation’s eight securities exchanges is under the jurisdiction of the SEC’s Division of Market Regulation. Under the current system of the exchange as a DSRO, the SEC merely signs off on an exchange’s plans to enforce its own rules and regulations affecting trading practices and regulations.

But because exchanges have a unique status in the regulatory landscape, they are free to pursue infractions against individual firms and brokers but are held unaccountable in others, including their own personnel policy and compensation.

This is the blind spot in the SEC’s regulatory perspective.

According to the agency’s 1991 Annual report, the SEC Division of Market Regulation oversaw the activities of the nation’s eight stock exchanges, 8,600 broker-dealers, the OTC markets, and 15 clearing agencies.

Under the SEC’s full disclosure system, administered by the SEC Division of Corporate Finance, the system is supposed to work “to provide investors with material information, foster investor confidence, contribute to the maintenance of fair and orderly markets, facilitate capital formation, and inhibit fraud in the public offering, trading, and voting and tendering of securities.”

The Sprecher situation raises whether real disclosure is a reality or just a smokescreen. The individual investor’s best hope is with the very few NYSE’s independent board members. They may, and it is a big “may,” have the guts to make a difference.

In the NYSE’s own Corporate Governance Guide, the first page lists some lofty goals, including:

“Establish the appropriate “tone at the top” to actively cultivate

a corporate culture that gives high priority to ethical standards,

principles of fair dealing, professionalism, integrity, full

compliance with legal requirements, and ethically sound strategic goals.”

It’s clear Sprecher has violated the first two lines of this statement. Plus, top executive officers at most of the NYSE-listed companies would be fired for violating any of the goals listed in this single sentence.

So what is the NYSE board going to do? Defend the wealthiest guy in the room or strike a blow for the benefit of average investors?

[…] though the Justice Department found no wrongdoing in their case since it involved the use of SEC Rule 10b5-1, the Sprecher insider trading charges are especially problematic since he also is the NYSE […]

[…] were involved in an insider trading scandal earlier this year when Loeffler was accused of trading on information she received in a confidential briefing about […]