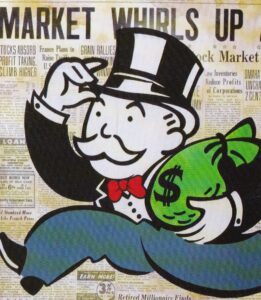

Trump and his gang plan to privatize the USPS, and possibly Social Security. This is an old plan of neoliberals who believe the free market system is the best allocator of services. But crony capitalism comes first.

When the U.S. Supreme Court increased the ability of wealthy donors to influence political campaigns and elections by raising the amount they can contribute to candidates, it signals that money and politics are now synonymous.

This means that campaign contributions from the nation’s wealthiest people will now influence all political offices at every governmental level. Loopholes in the ruling will also be exploited to funnel more money to fringe and mainstream candidates. Still, the net effect will be a shrill and acidic national political debate.

Writing in the New Yorker (“The John Robert Project,” April 3, 2014), Jeffrey Toobin said that while the existing donation limits (an individual’s maximum contribution of $250 and from contributing over $123,000 in total to multiple federal candidates in an election cycle) affect less than 600 people, the real danger is yet to come.

“So why is the case important? Because the language of Chief Justice John Roberts’s opinion suggests that the Court remains committed to the project announced most prominently in the Citizens United case four years ago: the deregulation of American political campaigns,” Toobin said.

In short, the U.S. political system is now for sale, and it comes at a time when the nation has one of the most significant wealth gaps in its modern history. This is the setting for a perfect storm and the emergence of a new plutocracy.

While the link between big money and big politics has been building for years, yesterday’s Supreme Court decision means that average citizens will become even more politically and economically disadvantaged and less politically powerful in this new American society. It also creates two classes of citizens: those with almost unlimited political influence (the best government money can buy) and those who have nearly none.

“We have made clear that Congress may not regulate contributions simply to reduce the amount of money in politics, or to restrict the political participation of some in order to enhance the relative influence of others.”–U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Roberts

The Widening Wealth Gap

Since the 1970s, the average real wage of most Americans has remained stagnant, while the wealthiest Americans have accumulated geometrically more wealth. In a new book, “Capital in the Twenty-first Century,” French economist Thomas Piketty analyzed the top income data from 30 nations and compared income inequality from 1913 to 2003. (See the article, “Forces of Divergence,” by John Cassidy, the New Yorker, March 31, 2014, p. 69)

In the U.S., Piketty’s research showed that before and after the 2008 recession (which lasted from December 2007 to June 2009, the longest since the Great Depression), the top 1% of households took over 22% of the nation’s total income, the most significant amount since 1928. In practice, this means the CEOs of Fortune 500 companies are paid 200 times more than their average worker in the same company. The annual salary of Apple’s CEO ($378 million, comprised of stocks, options, and salary), for example, was 6,258 times the wages of an average Apple employee. While an average Walmart worker makes $25,000 annually, that company’s CEO made $23 million in 2012.

For the average worker, the story is not getting any better. In my book, (How 401(k) Fees Destroy Wealth and What Investors Can Do To Protect Themselves), I noted that from 1979 to 2009, productivity grew by 80%, but the hourly wage only increased by 10%. Even then, all the wage growth happened from 1996 to 2002, reflecting the solid economic growth of the 1990s before the high-tech Y2K crash of 1999 to 2000.

Worse, real wages are not growing. Since 2007, wages have not grown. From 1973 until 2006, the average hourly salary for U.S. workers went from $18.90 to $21.34. according to the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), That translates into a meager 13% increase in 33 years or about 0.4% per year. If you factor in wages and benefits, the median worker’s pay package rose just 0.2% per year from 1983 to 1989. Even worse, from 2002 to 2007, worker compensation did not increase at all. This means the average worker’s pay has stagnated since the 1970s.

According to Lawrence Mishel, president of the EPI, stagnant wage growth due to globalization, the decline in union membership, and deregulation have all hit college-educated workers and those without degrees equally hard.

Other factors contributing to stagnant wages since the 1970s have been the rise of perma-temp workers, outsourcing, the rise in unpaid internships, increased technology and replacing entire job categories, and the intense competition for even the most menial jobs. All this helps explain why U.S. economic activity has grown 2.5% since the recession began in late- 2007, even with over three million fewer workers, according to the American Enterprise Institute.

Of course, having a financially insecure American workforce benefits employers. This is why Federal Reserve Board Chairman Alan Greenspan said in 1997 that workers with poor job security would be more reluctant to ask for raises. He said this would eliminate a major cause of inflation.

This same New Yorker article notes that the world’s richest 85 people have more wealth than the poorest 3.5 billion. These staggering figures led economist Piketty to say that “the consequences for the long-term dynamics of wealth distribution are potentially terrifying.”

Campaign Contribution Limits and Watergate

Given this dismal economic backdrop, today’s Supreme Court decision has an especially dire impact. Today’s decision upsets the campaign contribution limits imposed during the Watergate era in the court’s key 1976 Buckley v. Valeo decision. In this case, the court upheld limits on campaign contributions that Congress put in place in 1974 during the Watergate scandal.

Reflecting the sentiment of the Watergate era, the ruling held that contributions could be limited to prevent corruption or the appearance of corruption. At the same time, expenditures were considered a form of direct personal expression. According to the Washington Post, this decision led to the current system in which donors can give a federal candidate $2,600 per election but donate to super PACs, which must spend their money independently of candidates and parties.

Not surprisingly, the Washington Post reported: “Republican Party officials cheered the opinion. The ruling “is an important first step toward restoring the voice of candidates and party committees and a vindication for all those who support robust, transparent political discourse,” said Reince Priebus, chairman of the Republican National Committee, which brought the case with Shaun McCutcheon, an Alabama businessman.”

While Super PACS and loopholes certainly do not encourage “robust, transparent, political discourse,” it’s evident that big money has found an even bigger way to buy the best government money can buy.