“The system is presented as having such a mystique that apparent evil

becomes a kind of good.” — The Organization Man, William Wythe

When Jeff Sprecher, the Chairman of the New York Stock Exchange, and his wife, the sitting Republican Senator from Georgia Kelly Loeffler, were both named by the SEC in an insider trading scheme, it again revealed the double standard that applies to the rich and powerful.

The insider trading charges against Sprecher are especially interesting since he is both the CEO and Chairman of the company that owns the NYSE (NYSE-ICE), but is also the chairman of the NYSE, a publicly-traded company.

This dual executive role poses a huge problem to Sprecher since he is associated with an insider trading scheme. In the world of global finance, insider trading ranks at the top of financial crimes, along with embezzlement. Both involve a breach of fiduciary trust that taints the offender and their financial institution.

Even though the Justice Department found no wrongdoing in their case since it involved the use of SEC Rule 10b5-1, the Sprecher insider trading charges are especially problematic since he also is the NYSE chairman.

The NYSE is a Designated Self-Regulatory Organization (DRO) and can investigate and punish member firms and their top executives without SEC approval. As a publicly-traded company, the NYSE must comply with the same standards it applies to its own listed companies.

The big question is whether the NYSE can objectively investigate itself?

So far the NYSE has been silent on whether it will reprimand its own chairman, who also controls the NYSE board, as well as the parent company that owns exchanges worldwide. The board also has the authority, if they choose to use it, to punish or remove Sprecher. (The NYSE did not respond to requests for comment on this situation.)

While the insider trading charges against a global CEO are rare, the NYSE has faced this problem before when an errant CEO tried to eliminate any scrutiny of their $188 million executive performance from the NYSE Board.

This has many similarities to the Sprecher insider trading case, including how conflicts-of-interest, fiduciary violations, and ethically-compromised board members and executives, all show the NYSE is incapable of investigating itself.

One reason is board compensation. One member of the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE) board, which owns the NYSE, is Frederic Salerno, who makes $424,938 a year as a Lead Independent Director. Other ICE board members are also highly compensated and many own ICE shares.

Is History Repeating Itself?

In this earlier 2004 NYSE case, described below, Manhattan District Attorney Eliott Spitzer prosecuted any exchange employees who had a role in the compensation scheme, including the NYSE chairman and his senior VP of human resources.

For those who think that working in the human resources department is humdrum, Spitzer’s prosecution and subsequent jail sentence for an HR executive are rare.

But it shows that the top-level NYSE executives are capable of lying to the NYSE board in order for its chairman to receive a bonus of about $187 million, the largest ever paid to an NYSE employee.

In the Sprecher case today, the NYSE board should again be scrutinized to see how they handle insider trading charges and the appearance of impropriety against its own chairman.

They also should enact the same strict self-policing standards that apply to NYSE listed companies. If not, the NYSE looks like it adheres to a lower standard of corporate conduct. Then, it will face a replay of this 2004 scandal.

Greed and Deception at the NYSE in 2004

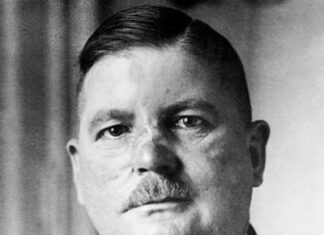

In 2004, Manhattan DA Eliot Spitzer sued Richard Grasso, the former CEO of the New York Stock Exchange, a former Director, and the Exchange, citing violations of New York’s Not-for-Profit Corporation Law in the award of an excessive compensation package.

The civil lawsuit comes after a four-month investigation by Spitzer’s office determined that Directors of the NYSE were misled about various aspects of the $187.5 million pay package awarded by the Exchange to Grasso.

The civil lawsuit comes after a four-month investigation by Spitzer’s office determined that Directors of the NYSE were misled about various aspects of the $187.5 million pay package awarded by the Exchange to Grasso.

In a related action, Spitzer announced settlements with an NYSE executive and an independent consultant who both admitted providing information to the board that was inaccurate and incomplete regarding the pay package Grasso received.

The suit asks a state court judge to rescind the pay package and to determine a “reasonable” level of compensation for Grasso. The suit, which names Grasso and Kenneth G. Langone, former chairman of the NYSE Compensation Committee, was filed in State Supreme Court in Manhattan.

The New York Stock Exchange was named in the suit because it failed to ensure compliance with the not-for-profit-law and made excessive payments to Grasso.

“This case demonstrates everything that can go wrong in setting executive compensation,” Spitzer said. “The lack of proper information, the stifling of internal debate, the failure of board members to conduct proper inquiry and the unabashed pursuit of personal gain resulted in a wholly inappropriate and illegal compensation package.”

Spitzer’s suit alleged that:

- The NYSE Board of Directors was misled on various aspects of the Grasso compensation contract.

Inaccurate and misleading information in the form of incomplete and incorrect analyses were provided to Board members. Frank Z. Ashen, a top deputy to Grasso, admitted providing “incomplete, inaccurate and misleading” information in documents to the Board. In one example, the Board was not aware of $18 million in the so-called Capital Accumulation Plan (CAP) bonus awards to Grasso for 1999-2001. In addition, Mercer Human Resource Consulting, Inc., a consultant asked to prepare a financial analysis of a proposed $187.5 million payment to Grasso, has admitted that its report to the Board contained “inaccuracies and omissions.” - The compensation formula that generated huge payments for Grasso was flawed and under Grasso’s control.

The compensation formula was inappropriately driven by comparison with the salaries of top executives in the world’s largest corporations. In addition, the investigation found that Grasso, in effect, set his own performance targets, which he easily exceeded. In any event, the NYSE disregarded its own formula on numerous occasions and awarded Grasso funds well beyond the formula’s product. - The compensation provided to Grasso was not “reasonable” according to state law.

New York Not-for-Profit Law requires that compensation for executives be “reasonable” and “commensurate with services provided.” In this case, however, the compensation far exceeded what would have been permitted by that standard. Indeed, the amount expended by the NYSE for Grasso’s compensation and benefits for 1999 through 2001 nearly equaled the NYSE’s total net income for those years. - Grasso’s dual role as regulator and NYSE employee raised a conflict of interest.

Heads of major Wall Street investment banks were also members of the Compensation Committee. During the same period, they approved Grasso’s excessive pay packages they had joined him in a private SEC-sponsored meeting at which they were assured that analyst conflicts of interest were “for the industry to resolve” without regulatory action. This same situation may apply to Sprecher today.

The complaint also cites the testimony of one compensation committee member who privately expressed concern about a component of Grasso’s proposed compensation for the year 2000 and, subsequently, was personally confronted by Grasso.

The director testified that he “was taken aback that my hesitancy was reported immediately (to Grasso).” The committee member, who probably was an executive of an NYSE member firm, ultimately approved Grasso’s compensation package, said: “Thank God I escaped that one. This man was also our regulator, and I’m a member of the New York Stock Exchange … and when he’s … your supervisor or your regulator, you have to be careful.”

Under the terms of his settlement with the Attorney General’s office, Ashen will return $1.3 million to the NYSE. Mercer Human Resources, Inc. will return the fees it charged the NYSE in 2003.

Spitzer thanked the SEC for working with his office on the investigation.

The Attorney General is responsible for enforcing the Not-for-Profit-Corporation Law (NPCL), which governs New York not-for-profit corporations and the conduct of their officers and directors. NPCL Section 720(b) authorizes the Attorney General to commence an action against a director or officer of a not-for-profit corporation to “to compel the defendant to account for his official conduct” with respect to “the neglect of, or failure to perform, or other violation of his duties in the management and disposition of corporate assets.” The law further authorizes the Attorney General to seek recovery of unreasonable compensation.

The investigation was led by Deputy Counsel Avi Schick with Assistant Attorneys General Bruce Topman, Robert Pigott, and David Axinn and Legal Assistant Pascual Noble.

[…] NYSE chairman Richard Whitney was involved in an embezzlement scandal. The second was in 2004 when NYSE Chairman Richard Grasso was accused of violating New York’s Not-for-Profit Corporation Law and misleading its board of […]

[…] began coming under more intense criticism from institutional customers who complained that exchange specialists were engaged in insider trading or front-running orders in equity and currency markets and were not […]