Part I:

How professional real estate developers push

large projects through a captive city council

Boca Raton, Florida, is being transformed. It is the new home of the nouveau riche, transplants from the north, and an increasing number of predatory capitalist professions. And it is not for the better.

Luxury real estate developers are targeting the city of 96,000 (as of 2021) in high-powered campaigns to push through new, expensive developments (condos, single-family homes, mixed-use developments) into an already crowded city grid where builders covet every square foot of land.

One building expert said there will be 5,000 new homes within Boca Raton city limits in the next few years. This will create more traffic congestion, bicycle fatalities, and a diminished quality of life. It could also mean lower home prices and higher taxes as the city strains to keep up with new infrastructure, more cars, and more people.

Given the high-profile case of real estate developer and former president Donald Trump, average citizens have every right to be concerned about whether there is such a thing as an honest real estate developer. It is becoming more complicated to find developers who keep their promises, adhere to existing zoning rules, and don’t ask for special favors from elected officials and regulatory boards.

However, the current record in South Florida–extending from West Palm Beach to Miami– for conducting ethical business places the burden of proof on real estate developers and elected city officials. The lure of profits outweighs good business practices. The reality is that significant real estate developments are costly and carry many risks. Land, acquisition, site development, architects, legal, consulting, financing, insurance, and material costs are expensive variables that rise with interest rates and inflation. Expenses accumulate daily, so when an approved and financed project gets the green light, time is of the essence. This is because profit is paramount. Every square foot and every construction day must be maximized.

The Developer’s Harsh Reality

To get a project off the ground and into the marketplace as fast as possible, developers work with consultants, architects, PR people, lawyers, lobbyists, local politicians, and political facilitators to get plans approved quickly and, very often, with special considerations.

But often, these are not straightforward large project plans that fit neatly into an existing survey plot of land that fully complies with current zoning regulations.

The most significant projects often demand special zoning considerations, variances, and other special concessions from city or county governments to maximize profits. Worse, many deals are done behind closed doors or via opaque lobbying groups that don’t disclose their donors.

The influx of sophisticated real estate companies and their pressing need for special favors has also stressed election officials.

In 2021, the former mayor of Boca Raton, Susan Haynie, a Republican who held elected office in Boca Raton for more than ten years, was charged with four felonies, including the three counts of official misconduct, one count of perjury, and an additional misdemeanor of misuse of an official position. Over three years, she received over $330,000 from a local developer as she voted “on at least a dozen proposals that increased [the developer’s] property values.” In 2021, Haynie pleaded guilty and received no jail time, according to the Palm Beach Post. What was missing from the coverage was what happened to the $330,000 she received in kickbacks.

The real estate development history of Donald Trump in New York has also focused more attention nationally on developers and how they can often push legal limits to get their projects completed as quickly and cheaply as possible. As the October 2023 trial of Trump in New York shows, real estate development is a shady business. Temptations to cut corners increase because large projects carry massive construction and financing costs that then require atmospheric sales prices to produce a profit.

Today, south Florida’s extensive developments—starting in west Palm Beach to the north and going south along the coast through Boca Raton, Deerfield Beach, and all the way south to Pompano Beach in Dade County–can swamp small zoning departments with special requests and demands for an excessive amount of time from city councils, building inspectors, traffic departments, and city attorneys.

Worse, Florida Governor Ron Desantis has invited businesses into the state because they can be “free.” This has dangerous implications because Florida is already the nation’s fraud capital, so it’s unclear what “free” means. Free to do business in the loosest way possible? Are you free to cut corners when it comes to business practices? Free because you don’t have to wear a mask to prevent COVID-19? Free, so you will have trouble getting an abortion? Free so you can be intimidated for your sexual orientation? Or free so you can dispute American history. Most importantly, it looks like “free” means little or no regulation in Florida.

This means predatory capitalist businesses, such as real estate developers, hedge funds, and private equity, can come to Florida, not pay state income taxes, and have reduced federal taxes thanks to the controversial carried interest tax loophole. For real estate developers, South Florida is also the place to repackage parcels of land, manhandle local city officials to get variances and special favors, and benefit from cheap construction costs compared to many other areas around the U.S.

The Boca City Council’s Flawed Vision

In Boca Raton, the city council has adopted the unproven vision that Boca will be a new financial center that will propel growth. But there is no evidence of that.

Hedge funds, private equity, and real estate are not labor-intensive industries. Managers in these industries prefer to spend money on technology rather than people, and support-level jobs are few. Hedge funds and private equity depend on federal regulations and market fluctuations. Private equity is known for destroying jobs, not creating them. Plus, the city council’s vision is based on wealthy people moving here for a better quality of life, just as the city is decreasing its quality of life for many other residents by making it more congested.

“Free” in Florida may attract some people. Still, the word also has another meaning: Florida is the fraud capital of the U.S. These frauds range from tax evasion to shoddy construction, running fake charities and tax-exempts, and real estate scams. Fraudsters are now welcome in Florida.

A government lawyer said in an article by Jasper Craven in the Nation (September 2022) that states with strict consumer protection and oversight of nonprofits noted that when they prosecuted fraudsters, they moved to other, friendlier states with lax oversight.”

New Developments, Sky High Prices

To maximize their profitability, developers are not building houses for average citizens. The high costs of construction and land require a significant return. That’s why a recent Palm Beach Post article cites two significant condo developments, two hotels, and two large office complexes focused in the downtown area, east of Federal Highway. The approximately 585 planned new luxury residences, including apartments and townhouses, are not for the common folk.

The new condos range from $2 million to $10 million in one development, while townhouses start at $4.85 million. In West Boca, the unincorporated area of Boca bordering Rout 441, new residential products, often starting at $900,000, have distinctive large fountain displays, a large clubhouse, and high HOA fees. For instance, according to a real estate website, in the 11 Valencia communities in Palm Beach County built by GL Homes, the HOA fees average about $670 a month. According to Redfin, this compares with a median sales price of existing homes in Boca Raton of $623,000 as of August 2023. The cost of new construction homes in Boca carries a median listing price of $787,000, according to Redfin. And the HOA fees for downtown Boca condos can reach thousands of dollars monthly.

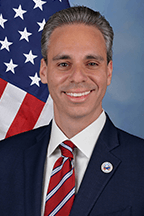

Boca Mayor Singer’s Odd PAC

The Republican mayor of Boca Raton, Scott Singer, has publicly stated the need for “more meaningful open space…that now ensures more open space for downtown projects” and “protecting against overdevelopment.” Similarly, the four members of the Boca City Council have publicly stated they favor green energy and sustainability projects.

But Singer and the city council have been very welcoming to developers. This could be why two recently formed political action committees (PACs) were founded for Singer’s benefit, which received about $165,000 in contributions, according to a report in Boca Magazine. Oddly, it’s not clear why Singer needed a PAC since he was elected with about 90% of the vote and has not announced any plans to hold future public office.

It’s also odd that the most significant contributors to Singer’s PAC were from real estate development companies or construction firms. Neither Singer nor the people named as heads of the PACs commented to Boca Magazine about the rationale for the PAC or how someone would use the money. Yet on his official city website, Singer said he believes in more government transparency and a green future for Boca.

If Singer does not run, the Florida Division of Elections says that “The political committee must disburse the funds in the manner that the committee indicated it would dispose of residual funds on the Statement of Organization of Political Committee (Form DS-DE 5), which is on file with the filing officer.”

Is Boca’s Planning & Zoning Board Objective?

But that’s not the whole story. While the Boca Raton City Council and Mayor Singer talk about addressing congestion and downtown open space, the actions of the seven-member Boca Raton Planning & Zoning Board tell a very different story.

Boca’s descent into congestion and developer control began in 2016 when the Interim Design Guidelines (ITG), approved in 2016 by the now-disgraced former mayor Haynie, caved into the developers’ demands.

According to Boca First, the city’s top-notch community watchdog group, “These guidelines, heavily influenced by architects for large development companies, established new rules for downtown construction. The IDG ordinance amended it to give developers a wider latitude to build bland buildings. IDG buildings were allowed to go higher, parcel sizes smaller, and more types of projects automatically green-lighted as a “right to build” with less input from city planners.”

In another article focused on developers’ intent to build more assisted living facilities, Boca First summarized the developer’s goal as “rather than develop expensive land already zoned properly, the name of the game is to grab lower-cost land and get it re-zoned” so the developer could build his project at a cheaper cost.

How bad is the situation?

“Unfortunately, if social media is a true indication, our Mayor and City Council are no longer relevant to the broad base of residents. They are viewed as puppets of developers who care more about visitors than residents. It’s easy to see how people get that impression,” according to Al Neibauer, a veteran real estate journalist and contributor to Boca First.

Neibauer also pointed out a zoning feature unique to Boca called “office equivalent space,”* or the 175-page Ordinance 4035. Under this land use management concept, the city limits the amount of construction in the downtown and the type of land used, such as retail and residential. However, the fine print in the ordinance allows developers to borrow buildable space from other city districts and swap land use types to be applied to a new project. As a result, specific caps on development can be exceeded.

One example is a proposed hotel in Mizner Plaza, a pedestrian-friendly shopping and retail area, where a local developer has offered a 12-story hotel rising 120 feet and located about a mile from the ocean. There is already an approved project, Aletto Square, in the same area that will increase traffic six-fold in the small downtown area and create more parking problems, according to Neibauer. Combined, these two projects will inundate downtown and violate the intended cap for new construction.

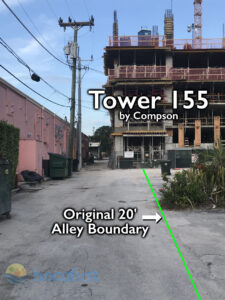

“Boca is a developer’s paradise,” Neibauer said. For example, he cited a 12-story residential project where the developers and a land use lawyer owned four parcels separated by a public street and alley. To make the project more profitable, the developers asked the city to give them the street and alley to connect the parcels. The developers got their way, and now Boca will have a concrete building spanning two blocks, while local businesses and citizens lose a street and an alley.

This has happened before. Neibauer cited the example of what happened when the mayor and two other Boca City Council members gave a developer three feet of a public alley. The result looked like this:

According to Neibauer, uncontrolled development will only get worse under the state’s Live Local Act, which encourages affordable housing. Developers can get substantial tax savings by building a minimal number of affordable units.

The Act allows projects denser and higher than allowed in some zones without requiring resident input. This can result in 12-story buildings mixed with single-family, duplex, and townhouse neighborhoods. These developments can have 90%-multimillion-dollar luxury units and just 10% affordable 400 square feet each.

Neibauer also noted the difference between long-time Boca residents, who grew up in a low-density, quaint Florida town, versus newcomers and snowbirds from large cities accustomed to high-rises and dense traffic. “The new residents don’t care about the character of the town. To them, it’s financial, so if they see a small condo going for $1 million to $2 million or leased for over $10,000 a month, it doesn’t phase them.” But this view is not shared by long-time Boca residents who do not want public space, such as streets, alleys, and wetlands, commandeered by developers for their private use.

The West Boca Congestion Fiasco

Meanwhile, the push for more luxury homes has moved to west Boca Raton (west of Florida’s Turnpike between Delray Beach and the Broward County line.) Homes here, miles away from the Intracoastal and ocean, have historically been more affordable. But no more. Supply and demand, combined with a few large tracts of land for development, has created a more visible, contentious power struggle between a prominent local home developer, GL Homes, and the county.

The latest battle is between local conservationists who want to save Palm Beach County’s Agricultural Reserve Area from a GL Home development that would allow the company to build 1,000 luxury homes starting at $1 million. After a prolonged political lobbying and PR campaign, the local county commission caved into GL Homes and approved sending the plan to the state for review. This happened after “the county promised voters in 1999 taxed themselves $150 million to buy land in the reserve and keep the coastal farm belt from becoming suburban sprawl,” according to a report in Boca Magazine.

Boca Raton’s Contentious Growth History

While Boca Raton today is suffering a death by 1,000 cuts from sophisticated real estate developers who are building massive projects within inches of the maximum allowable space and pushing height limits, the city and the state of Florida in the 1970s adopted a very different pro-average homeowner position on urban density and land use issues.

A thesis published in 1977 by an FAU student, Patricia L. Cook, recounted that in 1972, Florida passed the Land and Water Management Act. This Act “contained a comprehensive policy to supervise local planning.” The Act also spurred Boca Raton citizens to address urban sprawl and population density issues, eventually resulting in a landmark lawsuit called the “Boca Growth Cap.”

The Boca Growth Cap, introduced in 1972, would limit the city’s population. The Boca Cap, as it became known nationally, was an amendment to the city charter that placed an absolute limit on population and housing in the city to 40,000 homes. Under the Growth Cap, Boca’s population could not exceed 105,000. Proponents of the Cap said they wanted to preserve the city’s low-density character to maintain the town’s quality of life.

The cap was enacted as Boca saw the city population increase from 6,901 in 1960 to 29,539 in 1970, an increase of over 300%. In 2021, the city had a population of 95,787.

Re-zoning actions also accompanied the Growth Cap. The paper stated, “Beginning in the 1960s, small groups of homeowners opposed what they regarded as the continuing trend of re-zoning areas for multi-family dwellings that had previously been zoned for single-family units.” A conservationist group, the Royal Palm Audubon Society, also supported the cap and the need to preserve the wetlands.

As a precursor of what would happen 51 years later, the paper said, “Palm Beach County has become involved with the city in a conflict over zoning authority in the reserve area west of Boca Raton. In effect, the city has attempted to use its designation as a regional provider of water and sewer services as a lever to control densities.”

The cap proved controversial, and by 1974, it was being challenged in court at the state and federal levels. At the state level, three developers, including the Arvida Corporation, contended, among other things, that a city could not limit its population. The City of Boca Raton countered that “control of density is a legitimate municipal function” and that the local community governs zoning matters.

Ultimately, in 1977, the Boca Cap was ruled unconstitutional by a Palm Beach County Circuit Court judge. That deflated the push for citizen activism for many long-time Boca residents.

Predatory Capitalists Come To Boca

Today, Boca Raton is home to a new group of companies that many consider the latest form of predatory capitalists. These include hedge funds, private equity firms, and real estate developers who are taking Ron DeSantis up on his offer to work in a “free” state where regulations can be bent to fit the profit opportunity.

All these companies are looking for “the edge,” a trading term that means they have a benefit or material knowledge that will reduce their risk and get them a higher profit than a competitor.

These investment businesses also benefit from the controversial carried interest tax loophole, where income is taxed at the preferential rates covered as investment income instead of ordinary income taxed at a high rate.

Critics of carried interest say the loophole exacerbates income and wealth inequality. It also produces excessive political and financial power in the hands of a few whose main concern at all costs is profit and getting the advantage over their opponents. This is true in trading, between competing private equity firms trolling for wealthy clients in a dwindling pool and developers who have to steamroll projects through anyone who makes the slightest move to oppose them. So when developers see an opportunity, they can bring in a team of specialists whose expertise is to eliminate regulations that prevent them from seeking maximum profit at the lowest risk.

The financial services industry has been an expert in sandbagging all pro-consumer regulations for decades. Financial industry lobbying groups (comprised mainly of hedge funds, private equity, real estate companies, mutual funds, investment banks, money managers, and insurance firms) are on record as lobbying against the Consumer Finance Protection Board, diluting fiduciary standards, and making financial services more opaque to investors.

So, as Boca Raton goes through another spasm of population expansion, it will again highlight the political power gap between take-no-prisoners real estate developers against an understaffed and all too compliant local zoning board members and weak city council.

As for the taxpayers in Boca Raton, the reality is that more congestion could decrease home prices or, at the least, make the city less attractive. Many cities have learned that there is a cost to over-development.

In the interim, residents will see more new luxury high rises and luxury homes in the city grid where street expansion is impossible, traffic will increase, and taxes could rise to pay for added infrastructure and maintenance. All this will happen even as elected officials swear they are pursuing a Green Agenda. This could be true because green is the color of Mother Nature, but it is also the color of money.

*Equivalent Development space, an arcane term and one used only by the city of Boca Raton, as defined in Ordinance 4035, “means that total amount of development authorized by this amended Development Order as calculated by use of the land use intensity equivalency factors set out in this amended Development Order for adjusting from one land use category to another with appropriate credit for demolition or replacement of existing buildings and uses.”